I would like to share with you an excerpt from the work The Prophet (1923, Finnish Annikki Setälä 1968) by the poet Kahlil Gibran (1883–1931). Maybe you are already familiar with it:

Your children are not your children.

They are the daughters and sons of Life's longing.

They come through you, but not from you.

And even though they live with you, they still don't belong to you.

Give them your love, but not your thoughts.

Because they have their own thoughts.

You can take care of their bodies, but not their souls.

For their souls dwell in the abode of the dawn,

where you cannot go, not even in your dreams.

You can try to become like them,

but don't try to make them like you.

For life does not go back and does not dwell on the past day.

You are the bow from which your children are shot as living arrows.

The archer sees the end of the endless path and

He will bend you with His power

so that His arrows will shoot far and fast.

Bow in the hands of Sagittarius with joy.

For as He loves the arrows that fly,

so He loves the bow

that is steadfast.”

I think the passage is about the fact that we are born into this world free; we don't even belong to our parents. Today, however, I am not left to ponder the meanings of the poem, but the story of immigration, internationality, multilingualism and the power of social support that lies behind it.

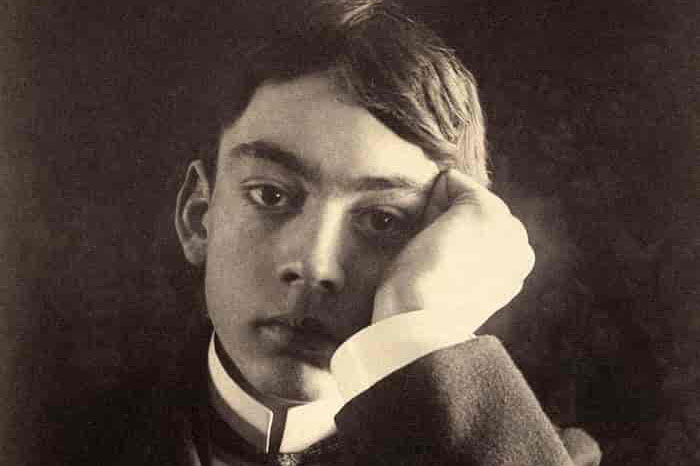

Gibran is known as a Lebanese-American writer and artist. Not yet familiar with Gibran's own story, I assumed the original language of the poem to be Arabic. The author is known in the West as Kahlil Gibran. It is an abbreviation and Latinization, i.e. a translation into the Latin alphabet of his official name, which when written in the original language looks like this: جبرن خليل جبرن . A more correct Latinization of the name would be Gibran Khalil Gibran.

Gibran was born in what is now Lebanon. At the age of 12, he moved with his mother to Boston after a relative. It was home to the second largest Syrian-Lebanese community in the United States at the time. According to some sources, the family fled Ottoman oppression, that is, arrived in the United States as refugees. Gibran lived, studied and later worked at least in Beirut, Paris and New York.

After settling in Boston in 1895, the young Gibran started in a special class at a school where immigrant children were taught English. In addition to this, Gibran began his art studies at the nearby settlement house, Denison House, which aimed to help poor immigrant and urban families to improve their living conditions. (By the way, Aurala is Turku's own settlement house, of which there are over forty around Finland!).

So Gibran's art career began with settlement activities. Florence Pearce, the settlement house's art teacher, drew attention to the boy and introduced him to art supporters. During his career, Gibran had several supporters and patrons, without whom he would hardly have become one of the world's best-selling poets. There is power in networking.

Gibran initially wrote in Arabic. He later switched to English on the advice of his supporter Mary Haskell so that his writings could become known worldwide. This goal was achieved. Annikki Setälä's Finnish translation of Gibran's most famous work The Prophet was published in 1968. Since then, two more recent Finnish translations of the work have been published.

Gibran was of Arab and Maronite background. Maronites are Christians who have their own independent position within the Catholic Church. Gibran has been called the "midwife of the new age" and the "prophet" because he wrote life wisdom independent of world religions and criticized both secular and religious authorities. With these merits, he also got into the disfavor of the Maronite leaders.

Gibran died in 1931 in New York and was later buried in his hometown of Bsharri, Lebanon. He bequeathed his future book fees to the development and improvement of his hometown.

World Refugee Day was celebrated on June 20. That day has already passed as I write this, but this blog post will be published in time for Poetry and Summer Day, which is celebrated on July 6. Perhaps, when we stop at Gibran's words, we can filter the thought to his life story as well. I am left to think about what kind of immigration stories we are building here in today's Turku and how we could push each other forward in life, in new directions, like a spring.

Mint Tarkiainen

The author is a social worker (higher MA), a solution-oriented brief therapist and an expert in multiculturalism, who works in Aurala's development project Family work and support for immigrants (STEA 2019–2021).

Life stages of Kahlil Gibran have been collected for this article from various online sources.